by Korin Swann

“Moreover, although both mind and object appear and disappear within stillness, because this takes place in the realm of self-receiving and self-employing (jijuyu) without moving a speck of dust or destroying a single form, extensive buddha work and subtle buddha influence are carried out. The grass, trees and earth affected by this functioning radiate great brilliance together and endlessly expound the deep and wondrous dharma. Grasses and trees, fences and walls demonstrate and exalt it for the sake of living beings, both ordinary and sage; and in turn, living beings, both ordinary and sage, express it and unfold it for the sake of grasses and trees, fences and walls. The realm of self-awakening and awakening others is fundamentally endowed with the quality of enlightenment with nothing lacking, and allows the standard of enlightenment to be actualized ceaselessly.

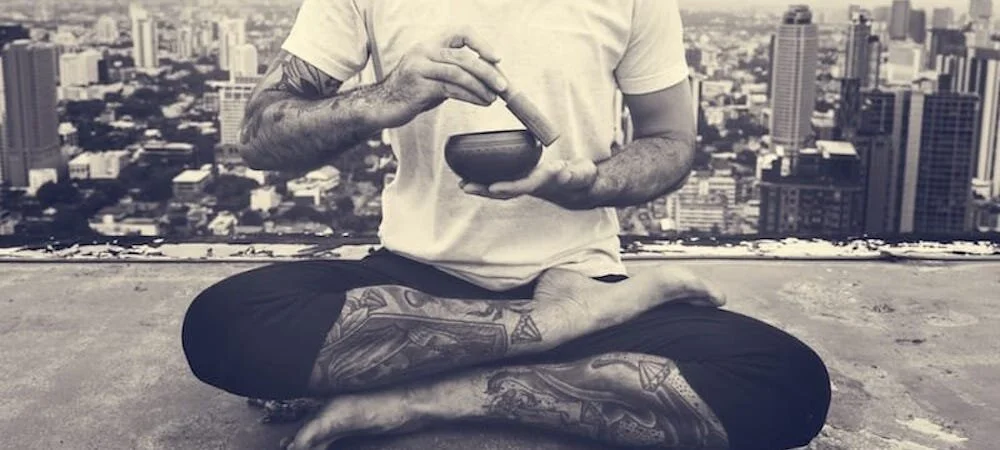

Therefore, even if only one person sits for a short time, because this zazen is one with all existence and completely permeates all time, it performs everlasting buddha guidance within the inexhaustible dharma world in the past, present and future. (Zazen) is equally the same practice and the same enlightenment for both the person sitting and for all dharmas. The melodious sound continues to resonate as it echoes, not only during sitting practice, but before and after striking sunyata, which continues endlessly before and after a hammer hits it. “ Master Dogen’s Zazen Meditation Handbook, translated by Shohaku Okumura and Taigen Dan Leighton

This passage brought up many questions for me when I first read Bendowa. I could see how grass, trees and earth might expound the wondrous dharma, but fences and walls?

We know of witness trees that were present at Civil War battlefields. In Austin there is an oak tree that witnessed the gatherings of the indigenous people who lived in the area. That oak was attacked by a person, poisoned, but it survived and is making acorns again. What its awareness is I cannot know, but that oak is about 500 years old and has seen so much. We know now that aspens are not single organisms but groves that are all clones and connected underground. Our understanding of these organisms has shifted radically during my lifetime, and will no doubt continue to grow. We can only experience these trees with our senses and intellects, rather than as they experience themselves, but their majesty and age provokes us to imagine ents and entwives, mystical sentient beings with their own culture and history. But fences and walls?

Surely they are insentient and thus I had to wonder how they could demonstrate the wondrous dharma.

What is ‘wondrous dharma’? The term in Japanese is myoho. Myo means ‘something strange’ and something we cannot grasp with the intellect. Shohaku Okumura says it also means something human beings cannot create. Ho is dharma, of course. We can’t devise it or create myoho with our powerful intellects. It is already here, given to us, and we can only be aware of it, open to experiencing something beyond the capacity of understanding with the discursive, rational intellect.

And yet Dogen says fences and walls demonstrate the dharma. How? They are, after all, human creations. The pivot point is the awareness of the implications of sunyata, emptiness.

Okumura suggests Dogen is referring in this passage to a poem by Dogen’s teacher Tendo Nyojo. “The whole body of a windbell, like a mouth hanging in emptiness, Without choosing which direction the wind comes from, For the sake of others equally speaks prajna...” Translation by Okumura and Leighton

We have talked about emptiness a lot in the practice period just past. Emptiness means that all dharmas are empty of any permanent aspect, any separate self that is fixed or permanent. This is an idea foreign to those of us who grew up in the western religious and philosophical tradition. Whether you grew up believing in a soul, or in a Platonic ideal, you thought there was something fixed and permanent, some essence of you or perhaps ‘tree-ness’. Buddhism teaches there isn’t. But what is the implication of emptiness? Interdependence.

Every dharma is dependently arisen. Every dharma is interdependent, whether fences, walls, trees or grasses. We are all interdependent. Nothing arises alone. This is a basic tenet of Buddhism- whenever any phenomenon arises due to conditions, another phenomenon arises with it, due to the same conditions. So sunyata, emptiness, echoes before and after a hammer hits it. The conditions of the hammer striking existed before the hammer came into the room. The conditions of your zazen existed before you were born. The conditions are tied endlessly together in past, present and future. They are unceasing. Indra’s net goes on in the ten directions, and in the three times we talk about, past, present and future. It extends ceaselessly, without beginning or end, and is of a complexity we cannot grasp.

Those of you who attend the Tuesday night class may recall reading this quotation from Kobun Chino a few days ago. “I learned breathing from butterflies. One day I was sitting at Tassajara, and I felt in tune with the breath of everything. The trees were breathing. About twenty butterflies were sitting on hot rocks, very white hot rocks, with clean water cascading between them. The butterflies were all breathing at once, opening their wings, and I tuned them in. It was very fantastic to feel that. Where does breathing originate, what is the beginning and end of each in-breath, out-breath? Who, or what, is breathing?”

In Austin I sat for years bracketed by two live oaks, one in front and one behind the building. I often felt gratitude to them for breathing in the carbon dioxide I breathed out. They breathed out the oxygen I needed. Our relationship was intimate, and yet many of us spend our lives unaware of our deep dependence on the lives of other beings. We can’t even digest our food without the assistance of gut bacteria. But we get caught up in a dream of a separate self that is somehow entirely independent. We make decisions that have implications for the lives of others. We eat meat, and the Amazon burns. We turn the AC on, and the oceans rise. Our connections are profound and ceaseless, and yet the connections are beyond my capacity to grasp. We can only investigate the edges of them, and in our zazen remain open to our profound connection to those we understand as sentient and those whose sentience we do not yet understand. Remain open to the wondrous dharma as expounded by fences and walls, as expounded by the zazen bell, as expounded by the clack of my keyboard.