By Joseph Hall

Zen is clear that it is not about seeking happiness. Just telling a teacher that you practice zen to get happy will usually be met with a scowl and the words, “Zen is not a method of Self Improvement.” It’s not that zen has a problem with happiness, in fact Dogen even tells us that “Zazen (sitting Zen) is the Dharma gate of ease and joy,” so it can come as a relief to know that happiness is allowed. It’s just that the Zen masters of old knew the same thing that we all learn, that trying to be happy tends to get in the way of being happy. So while we don’t any emphasis on it, it does seem to be a useful barometer to give us some insights on our practice.

My own experience was that I started sitting to develop a sense of samurai-like focus but started to notice there were a lot more flowers than I had thought instead, and also that I had some choices I didn’t have before. I’m happier than I was but I think that depends on how you look at things. Literally.

A few years ago, I took part in a study on happiness conducted by Matt Killingswort at Harvard who was is trying to follow the trail of the wandering mind, specifically, he wanted to know what happens to our mood when we daydream. A few hours after I signed up, I got the first of 50 text messages which came at random intervals during the days, asking me questions like a three year old child... What are you doing? Do you have to that? Do you want to, what are you thinking about, who are you talking to, if you could jump ahead in time, would you?

In the 650,000 responses received, Killingsworth’s team discovered that the mind of the average human is thinking about something other than what they are doing 47% of the time. In any given moment, half of us are not really here. They also discovered that whether and where our minds wander is a better predictor of happiness than what we are doing. What they discovered was what the average Zen student already knows, the wanderings of the mind lead to lower levels of happiness and it doesn't matter whether we are replaying a bad memory or imagining ourselves on a pacific island; when our mind leaves the here and now, our sense of well being quickly fades. The researchers discovered that while fondly replaying the scene where the crowd went wild might elevate your mood for a short time, within fifteen minutes there is a measurable drop in happiness leaving us feeling worse than when we started. It turns out that daydreams and drugs both follow the same addictive trajectory.

The Study found that doing what we want to do isn’t so important as we might think. But being on task, being immersed in it is.

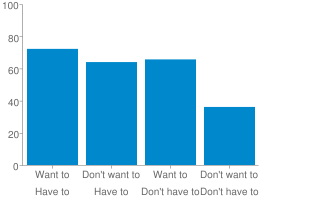

In the graphic here, my best moments were when I was doing what I had to do and when I wanted to. The times when I was doing whatever I wanted were a little less fulfilling. Surprisingly, doing what I had to do when I didn't want to do it left me just one percent less happy than doing whatever I pleased. The lowest points occurred when I was doing something I neither wanted nor had to do, which makes me wonder why I do such things.

The answer to why I was so happy doing things I didn't want to do was in word, immersion. The more immersed I was, the higher my level of happiness. My mood, shown in this nifty scatter chart, was directly correlated with my focus.

The Phenomenal Mind

For me, a question arose from this experiment, if focus is the answer, what do we focus on. The answer, at least for me, was catalyzed by a line of commentary in the research analysis. A scientist who was expounding on the capabilities of the human mind was discussing the phenomenon of mind and how the mind was a phenomenon that existed outside the limits of the physical world. Our neurons, he said, create an emergent system which creates something we call the mind. The phenomenal mind, he said, was larger than the brain, and is capable of imagining whole worlds all it's own. This, I thought, is where science and spirituality diverge and where I think Spirituality has it right.

The Phenomenal World

According to the Buddhist teaching, we live in a phenomenal world, which isn't always as good as it sounds. According to Buddhist cosmology there are two worlds that we live in - the absolute and the phenomenal. The absolute world is might be described as how things really are. The phenomenal world is how those things appear to us when when they appear in our minds. We can sense nothing about the absolute world, the phenomenal word, this interpretation is all we have.

This is why there is a Zen koan that goes,

If a tree falls in the forest,

And there is no one there to hear it.,

Does it make a sound?

Maybe a bell can help us understand this koan.

The Bell

When the bell rings, you think you hear a sound. There is no sound to hear but you hear it anyway, even though it dosen't exist. How can that be?

The bell is resonant, meaning that when is it struck, the energy is released in such a way that the surrounding air around is disturbed. The energy is absolute, so we can’t see it. But, as we know, the surrounding air is excited and moves outward. Perhaps it might strike an eardrum and the eardrum moves. We hear a sound and it carries a meaning to us. Maybe we think it's telling us to begin zazen and maybe a feeling arises. While we believe we understand that the feeling is separate from the sound we couldn't be further from the truth. When the bell is struck, the air moves in much the same way that it is moved by wind and in the absolute world, a truer representation might be to hear the bell as static or the noise that wind makes in our ears as it rushes by.

But our minds are constantly exploring the cosmos and just like the photos sent back from the voyager spacecraft, the details are not included in the original digital signal, but are inferred and created later. When the eardrum vibrates, the frequency is converted to a binary code and sent to the temporal lobe. The auditory cortex then creates an artist rendering, eliminating background noise and uses the binary data to create a sonar image of the world.

This is what we call sound, an image so convincing the we think it must exist outside our heads. The mind is so good at creating these images, that when we pick up the phone, which transmits only ten percent of the sounds carried by a recording, we recognize the voice immediately. We somehow still hear the missing 90% as if it were still there. The words we hear wrongly in a conversation, sound no different than the words that were actually there. The sound is you. Nothing like it is occurring outside our heads.

Sound is not anything that exists in the absolute world, but simply a representation of an available data source presented to us in a way we can understand. It is what computer programmers call a graphic user interface. When I think of bats, it just seems highly unlikely that their sonar is experienced as hearing. Bat brains, I suspect, would be better served by seeing sound than hearing it.

Contrary to popular belief the majority of our oversize brains are not devoted to intelligence, but simply to interpreting the senses, to conceptualizing the world that we see. This, it would seem is the most important this we do, our intellect and imagination require comparatively little space at all.

The Mystery

How is this related to our happiness?. The answer is simple. If focus reveals happiness, then it is good to have something to focus on. The world before our eyes is a mystery, and the more we immerse ourselves in this mystery, the more we find who we are. A shift occurs in the mind simply by trying to understand what is that we are seeing. This is true because while we ponder the mysteries of our mind and wonder how to find it, the world IS our minds, a particular movie made from our karma.

When you hear the bell you hear the sound of your karma.

That’s worth paying attention.