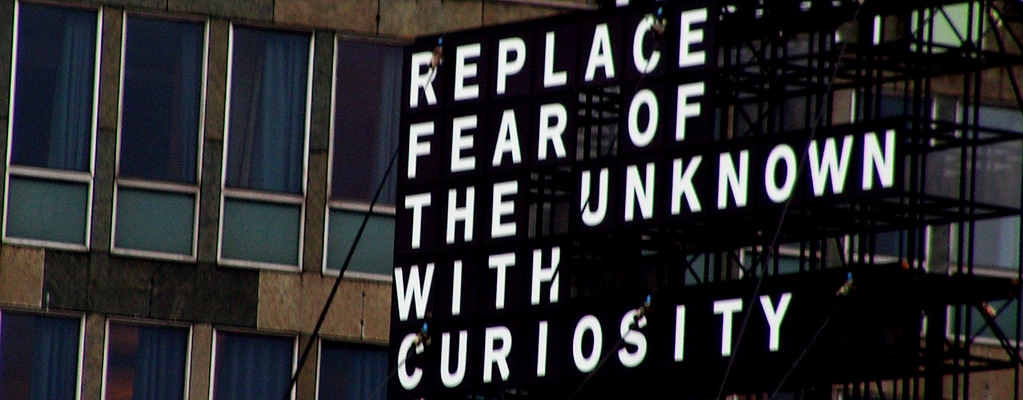

In Zen it is a dualism to discern the importance of any one thing, but Shunryu Suzuki uses the phrase 16 times in Zen Mind Beginners Mind so I think it's fair to say that the most important thing is to stay curious. Zazen, our meditation, is an open awareness or mindfulness practice, and however that term may be co-opted, zazen mind is the stance we are invited to take in all our practice. It is the place from which everything else can be revealed. When we get up from the cushion, our effort is to carry Zen Mind with us everywhere we go.

Of course, we are always losing our zazen minds, often the moment anyone speaks, the key turns in the ignition, or an alluring judgment calls to us. Catching ourselves, the idea that we need to return to the cushion to recapture a lost serenity can seem like a kind of truth. It is easy to forget that we are always one breath and three steps away from mindfulness.

As the millennium opened, and with it a dialogue between monastics and nueroscientists that would change both worlds, it became clear that in order to study something together, some definitions were needed. Even defining a thing can be revelatory. Compassion and gratitude were a little easier to define but when it came to mindfulness, the very fact that a definition is discursive sent everyone back to the drawing boards. Fortunately, a gateway opened with the idea that mindfulness is a mental state that arises naturally when concentration is focused on the present moment. At first everyone was happy with this definition and returned to the temples and laboratories to work on this. Quickly, however, this definition fell apart.

The monks had been a little skeptical all along. The scientists did some studies and discovered that snipers and truck drivers practiced these states deeply for thousands of hours in the course of their vocation, but clearly they were cultivating something else. Compassion, for example, was not arising the way one might hope in this form of practice. Clearly, there was something missing. A number of theories were put forward and while the sutras had a lot to say about clear mind, there were simply too many words. Finally, in 2004, Scott Bishop, working at the University of Toronto, noticed the missing condition - curiosity. The monks agreed that this seemed to describe their practice. The scientists conducted their studies and today this is largely accepted as what we are talking about when we talk about mindfulness.

Mindfulness is a natural state of mind which arises spontaneously whenever we do three things simultaneously: we pay attention, we focus that attention on the present moment, and we get and stay curious. Curiously, they never did manage to put mindfulness into words directly. Nueroscience can sometimes catch a glimpse of it on a scan, but zen mind remains mysterious. We can give you a map, but you still have to go there yourself to know what it is.

This explains why it can seem so hard to get back to our Zen Mind when we lose it. We remember the feeling and try to recreate it directly. So the monks were onto something when they talked about cause and effect and how this mind is more like baking bread. You can throw the ingredients into an oven but they need to work together to transform and arise. Fortunately, even though bread dough is intimately connected to its environment and involves many living beings, it is easy to learn to bake if we use the right ingredients, are aware of the temperature, follow the needs of the conditions and watch it arise.

How to create the conditions for mindfulness

Pay Attention. While there are moments when the world can seem chaotic, we always have the ability to pull the mind into some kind of concentration. Don’t worry if it is the right kind of concentration. You know the feeling of paying attention and how to be attentive.

Focus this attention on here and now. This might be a good time to take another look around the place you are in this moment. Look for things you didn’t notice before, listen for sounds that have been occurring beneath your awareness, what does this world you are in smell and feel like? Keep the focus wide, noticing both the sensations of your body and the light coming from far outside of it.

Get Curious. And Stay Curious. This is hardest part. In order to be curious, we can’t know anything and it can be surprisingly challenging to let go of what we think we know. Thus, it is going to be necessary to question everything around you, even reality itself.

Not Knowing is most intimate

Two monks met on the road…

Jizô asked Hôgen, “Where are you going?”

Hôgen said, “I am on pilgrimage, following the wind.”

“What are you on pilgrimage for?”

I don’t know.”

Jizô said, “Not knowing is most intimate.”

Hôgen suddenly attained great enlightenment.

In our quest for curiosity it might help to consider that what makes us human beings most unique is not actually our intelligence. Very little of our brain is dedicated to the intellect. The largest portion of the brain is dedicated to interpreting the visual and sensory experiences from which we create a model of the world that we conceive to be around us. Most of our neural activity is about making a movie. The most obvious thing about this world we see is that it is largely made up of color. So here’s the thing about color - you can’t trust it. And you can’t trust your mind either. I used to believe them both more than I do now and it even took me a few years of sitting in front of a wall in Austin before I really began to notice the most obvious thing in front of me - that this wall kept changing all the time. It was grey when we sat down for morning zazen, often yellow or amber when we stood up, and various greens, oranges, browns, and even purple in the evenings. This isn’t some psychoactive effect of too much zazen. When I taught Zen orientation at Jikoji, depending on the variables of clouds and the way light filtered through the trees, the room appeared to be yellow while the next week we all agreed that the room was decidedly peach. And yet we walk into a room week after week and somehow see a consistent color. If the color of the world we see is unreliable, then what are we looking at?

A little deeper in, if you have ever tried to calibrate a computer screen to represent the world, you will find it is a tricky and expensive process. Basically, designers in the world rely on Pantone cards which are compared to other cards and devices and everything is eventually connected to a set of master cards that try to preserve the truth of color as everything fades and shifts. The whole system relies on a set of standards based upon comparison to a source.

Color, in the human mind, is simply the way we represent the length of light rays captured by the human eye. As a species, we have evolved enough to know that you must match color by matching it to a source. And lest we forget, all our brains have to go on is the length of light rays. So not only may the green that I see appear different from the the green that you see, but it is highly unlikely that color is anything more than a useful way for us to conceptualize the world. It depicts something in a way that we find useful. Blue things, like the water and sky, provide us with the base elements that make our bodies possible, green things tend to offer opportunity for vegetables, food, etc, etc. Bright red is very rare in nature and is saved for crucial information, like blood. While this is a very useful and evolutionary way to navigate, we still have no method to confirm what anything looks like.

And it gets worse. Donald Hoffman, a Cognitive Scientist, in an interview published in The Atlantic titled ‘The Case Against Reality’ explains a growing view that, according to mathematical models, what we call the universe is unlikely to exist anywhere outside of our heads. Using the metaphor of the computer screen, the icon for a file is just something useful to us and nothing about it can be said to reflect the actual file. The content on the screen is not what the computer is and it is even questionable whether the processor is what the computer truly is. The deepest reality of a computer could be thought of as simply the flow of the energy moving through it.

Curiously, this is all sounds very similar to the Madhyamaka teaching that there are two forms of reality, what the Lakota called ‘The Real World and The One We Live In’.

So what are we looking at?

It may become quickly obvious that curiosity requires real bravery. If we realize that the world we thought was around us is actually inside of us, we can experience a visceral feeling of delirium. If what we see is indeed no more than practical representation of something else, then our ideas about it are all based on our unreliable perception. It takes real bravery to accept that this ‘delusion’ that Zen keeps talking about applies to everything we think we know. We are then left to wander a world where there may or may not be other beings who are wandering in their own versions of reality, possibly interacting with us in a place no one has ever seen. We could even be nothing more than rays of light creating this dream of life as simply a way to speak in metaphor. Anything is possible.

Knowing this, it pays to be curious about everything. If we don’t know anything, then everything is filled with wonder - even the views that arise to tell us that this is how it is. While they may not be true, everything hints at clues to a deeper mystery. And this world, which only exists in our minds, is our mind. And if we don’t know what this world is actually connected to, we can let go of our terror. All we can do is to do the best we can with the information that we have at hand. Our responsibility is not to be perfect, but to keep examining the world so we can do better. It also pays to try to be very careful in how we interact with the beings that we encounter. They are, in one sense, ourselves, and in another sense they may inhabit another world where we can have no idea what the effects of our actions may be. Kindness, then, seems the best way to go.

So our practice depends on our curiosity. While it can seem that we will be lost if we abandon judgements that seemed to help us compete, we are offered a choice to make in every moment. Since the deepest wish of every human being is to be known, our curiousity and openness to the truth of the moment can only serve to reveal the unthinkable possibilities that we never saw before. And it is extraordinarily useful to always be aware of the cracks in the world, the colors that shift, the way our projections don’t fit what we are hearing, and the way the small mind is always erasing and adjusting to make things fit into a story. It is through these cracks that the light comes through.

That is enough words. Like all words in Zen, these will need to be forgotten. Ours is a simple practice and the more we do it, the deeper we can go, the easier it becomes to get there, and the more frequently we remember how to access it. It’s a shift you can make in any moment. The most important thing is to stay curious. Just try it and watch what happens…